Given the long record of international agreements among states, it is reasonable to review three questions:

- Why do countries enter into international accords?

- What are structural barriers, or dilemmas, impeding our understanding of commitments and responsibilities of the signatories?

- What can be done to create more transparency and lift any "veil of uncertainty?"

To the first question, the answer is clear: states enter into global accords to avoid common aversions, and/or to pursue common interests. In the case of AI and its future, states are nearly uniform in seeking to avoid consequences that undermine security, safety, and sustainability.

To the second question, the answer is obvious but seldom acknowledged as such. All agreements (as all policies and laws) are written in text form—word after word, sentence after sentence, segment after segment—and thus all result in a linear representations of intents and commitments. Linearity per se does not represent that human existence, or social interactions, or agreements of any form on any issue. At a minimum, it is imperative to create transparency in the structure and content of the text in ways that accurately represent the details of accord.

This leads us to the third question: What can be done? The answer to this question begins with the use of analytics for policy—with special attention to visual representations—as we illustrated in section earlier

As noted earlier, policy documents are usually written in linear text form—word after word, sentence after sentence, page after page, section after section, chapter after chapter—which often obscures some of their most critical features.

Text cannot easily situate interconnections among elements nor reveal any underlying, "hidden" features. In response, our current research focuses on a computational approach to policy documents, with application to seminal works situated at the intersection of cyberspace and international law.

In the course of developing the methods for the Science of Security project, noted above, we explored the use of diverse policy texts as the "raw data" for analysis, such as:

- International Law for Cyber Operations: Tallinn Manual 2.0

- Budapest Convention on Cybercrime

Here we note briefly the analysis and results for the Tallinn Manual 2.0 and for the Convention on Cybercrime.

Tallinn Manual 2.0 for Cyber Operations

Despite major innovations in the construction and management of the Internet (the core of cyberspace)—or perhaps because of the remarkable expansion of its global reach—the international community is now on the verge of a major challenge: how to frame the relationship between international law and cyberspace. Our analysis of Tallinn Manual 2.0 on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Operations

Tallinn Manual 2.0 extends and supersedes the legal principals put forth in Tallinn Manual on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Warfare

For our research, the value-added of complexity coupled with computation—generic in frame and in form—is to (a) create transparency in the system, for the "whole" and for its "parts," (b) generate new ways of analyzing policy texts, (c) extend conventional views of the policy system, and (d) explore contingencies such as, "what if...?" Our approach consists of a chain of computational moves, each intended to generate specific outputs, and each designed to identify different properties of the legal corpus.

The text of Tallinn Manual 2.0 serves as the "raw data" for our investigation. In a document of nearly 600 pages, text-as-conduit imposes a form of sequential logic in an otherwise complex and interconnected set of directives.

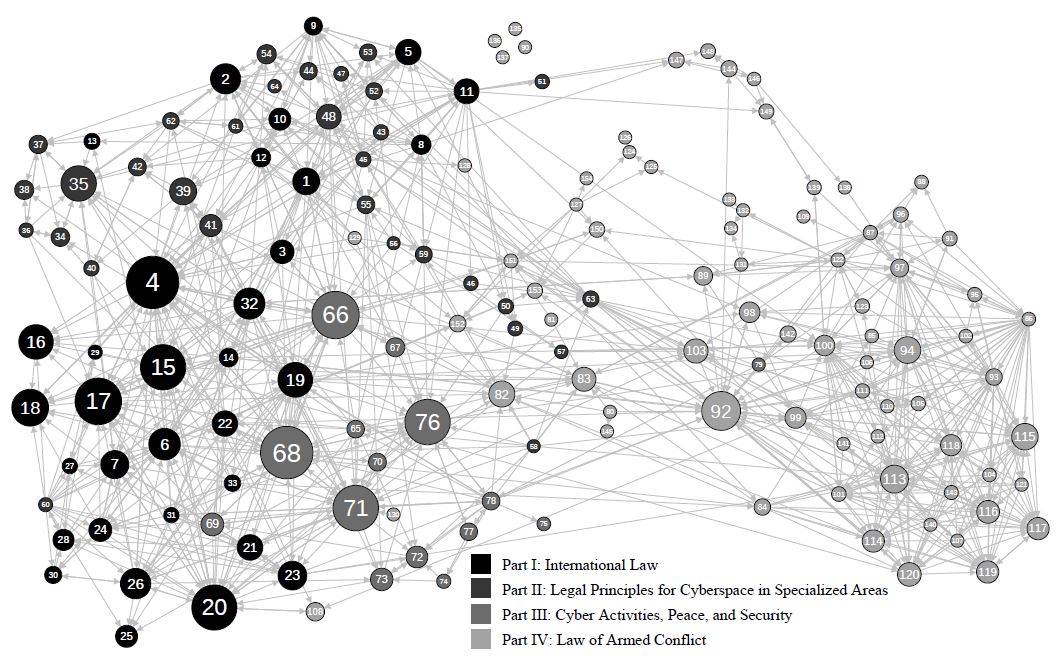

The results generate a range of system network views and point clearly to the statistical dominance of specific Rules, the centrality of select Rules or Articles, the Rules or Articles with autonomous standing, and the location of authority, as well as the feedback structure that holds the system together. None can be readily discernable in the text-form. Here we present one case to illustrate the process.

Here we note only one model of Rule dominance differentiates nodes by degree of centrality—determined by the eigenvector of a node that, itself, is shaped by the eigenvector of the Rules to which it is connected. The result is a network model of Rule centrality, derived from "neighborhood," yielding system-wide salience.

|

|---|

| Network Model of Tallinn Manual 2.0. Source: Choucri and Agarwal (2020). |

The figure highlights several notable features of the Manual.

First, the greatest concentration of high centrality nodes (five of the top ten) is located in Part I on International Law.

Second, although Part III—on Cyber Activities, Peace, and Security – hosts considerably fewer high-centrality Rules than Part I, some of its Rules attain notably high centrality scores. Rule 68 on "prohibition of threat of use of force" tops the list; Rule 66 on "intervention by states" ranks third, Rule 71 on "self-defence against armed attack" and Rule 76 on role of UN Security Council rank fifth and sixth respectively.

Third, only one high centrality Rule (of the top ten) is situated in Part IV on the "law of armed conflict," namely, Rule 92 located in Chapter 17 on "conduct of hostilities." This Rule defines a cyberattack as a cyber action that causes injury or death.

The logic of Tallinn Manual 2.0 assumes the absence of any significant difference between the structure of the international system and its legal principles on the one hand, and the networked system of cyberspace and its operational principles, on the other. In retrospect, it is clear that until very recently cyberspace has been a matter of low politics for the state system as a whole. Now that cyberspace has been catapulted to the highest levels of high politics, the international community as a whole faces a common dilemma: how to manage the cyber domain in a world where sovereignty is no longer the sole operating authority system.

Then, by definition, legal systems are structured to resist pressures for rapid change. Equally, by definition, all matters "cyber" transcend any efforts to limit the rates of change for any aspect thereof. We recognize that Tallinn Manual 2.0 was not designed to "fit" the characteristic features of cyberspace, rather to develop legal bases for its management in relations between states—during war and during peace. While states are increasingly able to control Internet access and content transmission, the principle of sovereignty is yet to be fully aligned with the extent to which global communication networks and cross-border information flows are managed by non-state entities.

More detailed analysis, in collaboration with Gaurav Agarwal, amply demonstrates how the principle of sovereignty pervades and dominates all aspects of International Law Applicable to Cyber Operations and, by extension, how authority is vested in the state (see Choucri and Agarwal [2020])

Convention on Cybercrime

The Budapest Convention on Cybercrime

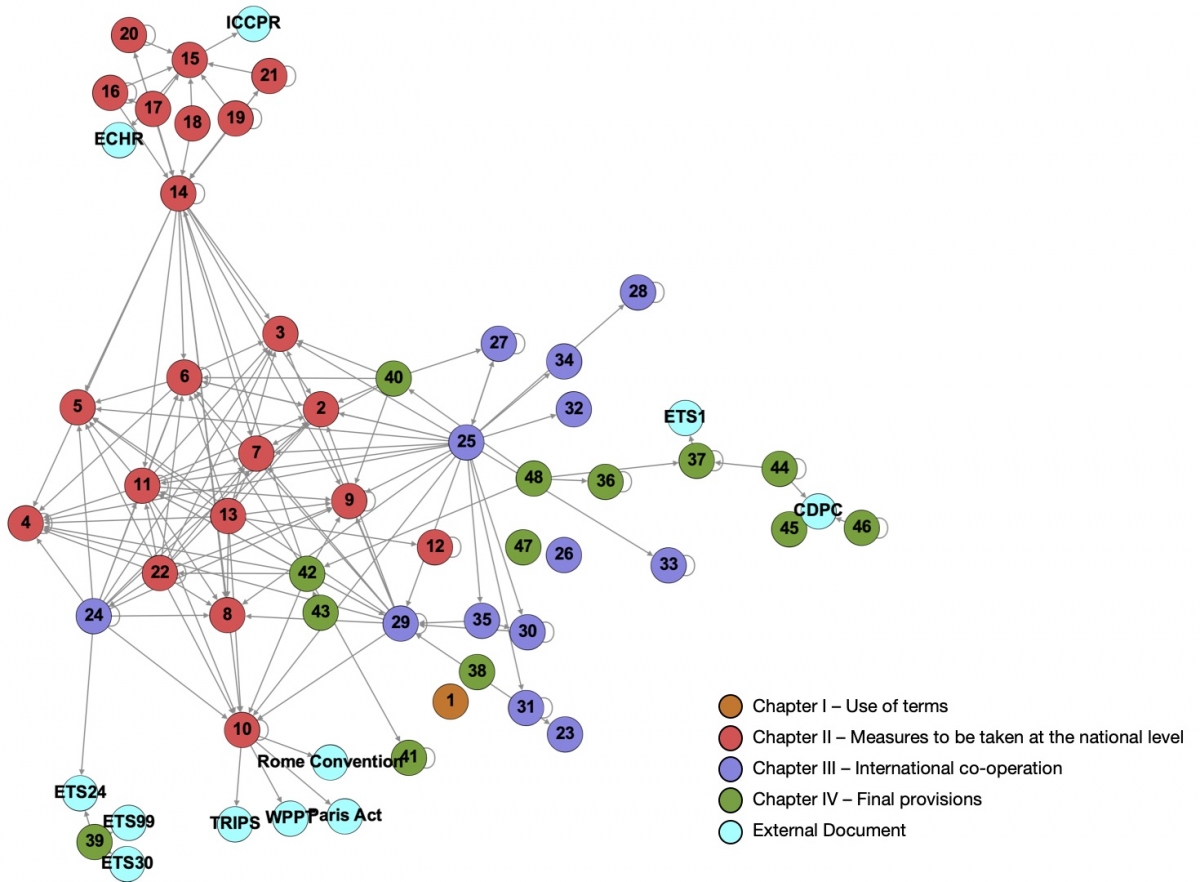

This figure below shows the components of the Convention and their connections. This is the simplest representation of text transformed into a network view. The nodes represent specific articles, and the lines are the connections as expressed in the text of individual articles. The color code on the right side provides the information required for differentiating between components of the Convention. Note that external documents are those referred to in the text.

|

|---|

| Network View of Convention of Cybercrime. Source: Choucri and Agarwal (2021). |

Even with the most limited form of visualization, we can identify at least three critical imperatives of the Convention that signal important directives for robust international agreements. Specifically, the Convention:

- Adopts an inclusive definition of cyber harm and damages, with no loopholes and no exceptions

- Focuses on national action and internal initiatives to reduce disconnects, build capacity, and enable collaborative responses

- Reinforces the scope of international accords by referring to, and leveraging, previous agreements, as well as extending cross-domain scope.

These imperatives will be especially important if, and when, the international community moves toward framing the next round of accords.

Reference:

- Choucri, N., & Agarwal, G. (2022). Complexity of international law for cyber operations

(Research Paper No. 2022-10). MIT Political Science Department.

- Choucri, N., & Agarwal, G. (2021). Complexity of international law for cyber operations

Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST), 1–7.

- Chocuri, N., & Agarwal, G. (2021). The Dynamics of Cyberpolitics (MIT CyberPolitics Lab Working Paper 2021-2). MIT Political Science.

The term “artificial intelligence” (AI) refers to the development of computer systems able to perform tasks and functions that normally require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, decision-making, language translation, and self-driving cars. Advances in AI have already altered conventional ways of seeing the world around us. This is creating new realities for everyone—with new possibilities, opportunities as well as new challenges, new threats, and new forms of disorder.

AI is also the focus of foreign policy—with both conflict and cooperation. There is a shared view that no single country can or will be able to compete, or meet the needs, of its citizens without increasing its AI capacity.

An initial step toward global AI accord, prepared by the Boston Global Forum—at invitation of the United Nations Academic Impact and associated with the UN Centennial—is in Remaking the World Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment. Below are selections from entitled, “Framework for an AI International Accord.”

There is a long tradition of consensus-based social order founded on cohesion and agreement, and not the use of force nor formal regulation or legislation. It is often a necessary precursor for managing change and responding to societal needs. The foundational logic addresses four premises: What, Why, Who and How?

What?

An international agreement on AI is about supporting a course of action that is inclusive and equitable. It is designed to focus on relationships among people, governments, and other key entities in society.

Why?

To articulate prevailing concerns and find common convergence. To frame ways of addressing and managing potential threats—in fair and equitable ways.

Who?

In today’s world, framing an international accord for AI must be inclusive of all stakeholders, notably:

- Individuals as citizens and members of a community

- Governments who execute citizen goals

- Corporate and private entities with business rights and responsibilities

- Civil society that transcends the above

- AI innovators and related technologies, and

- Analysts of ethics and responsibility.

None of the above can be “left out.” Each of these constitutes a distinct center of power and influence, and each has rights and responsibilities.

How?

The starting point for implementation consists of five basic principles to provide solid anchors for Artificial Intelligence International Accord.

- Fairness and Justice for All: The first principle is already agreed upon in the international community as a powerful aspiration. It is the expectation of all entities—private and public—to treat, and be treated, with fairness and justice.

- Responsibility and accountability for policy and decision—private and public: The second principle recognizes the power of the new global ecology that will increasingly span all entities worldwide—private and public, developing and developed.

- Precautionary principle for innovations and applications: The third principle is well established internationally. It does not impede innovation but supports it. It does not push for regulation but supports initiatives to explore the unknown with care and caution.

- Ethics-in-AI: Fourth is the principle of ethical integrity—for the present and the future. Different cultures and countries may have different ethical systems, but everyone, everywhere recognizes and adopts some basic ethical precepts. At issue is incorporating the commonalities into a global ethical system for all phases, innovations, and manifestations of artificial intelligence.

Jointly, these four features—What, Why, Who, How—create powerful foundations for framing and implementing an emergent Artificial Intelligence International Agreement.

Support for Global AI Accord

Based on the internationally recognized Precautionary Principle, a support system for AIIA Framework is expected to facilitate and formalize the Framework and its implementation. The individual supports include the following products and processes:

- Code of Ethics for AI Developers and AI Users.

- Operational systems to monitor AI performance by governments, companies, and individuals.

- Certification for AI Assistants to enable compliance to new standards.

- Creation of a multidisciplinary scientific committee to provide independent review and assessment of innovations in AI and directives for safe and secure application, consistent with human rights and other obligations.

- Draft of Social Contract for the AI Age to be supported by United Nations, governments, companies, civil society and the international community.

- Strengthen the World Alliance for Digital Governance to evolve into the global authority to implement land oversee the emergent AI accord.

End Note

The End Note addresses briefly some salient challenges, followed by highlights of opportunities, and concludes with a brief word of caution.

Technology and innovation are growing much faster than the regulatory framework anywhere, and most certainly at the international levels. Of course, we do not want regulations to change at the level of technological change—that would create chaos; you can imagine why and how.

We must now consider is the best precedent for global accord at this time? Is it nuclear power? Is it climate change? What are other high-risk areas? Usually, we address such questions long after the fact. But can we avoid this delay? At this point, we have an opportunity to seriously consider the properties of a global accord in AI before we are confronted with a major disaster.

Of high value, for example, is to consider and address the role of ethics in courses on innovations in AI, as well as ethics for all uses and users. So, too, is the importance of international law as relevant to AI.

Reference:

- Tuan, N. A. (Ed.). (2021). Remaking the world: Toward an age of global enlightenment. Boston Global Forum, United Nations Academic Impact. https://bostonglobalforum.org/publications/the-age-of-global-enlightenment/

- Choucri, N. (2021). Framework for an artificial intelligence international accord. In N. A. Tuan (Ed.), Remaking the world: Toward an age of global enlightenment (pp.27–44). Boston Global Forum, United Nations Academic Impact. http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/141737

Matters of ethics are becoming more salient at all levels of politics, almost everywhere. In the scientific community, ethics in AI is increasingly gaining attention. The fact is that the rate of change in AI innovations and applications are growing much faster that our general appreciation or of our understanding of content or of consequences.

Context

There are a large number of statements, but few ethical practices by countries, corporations, and individuals about that is desirable in the ethics domain for the broad area of Artificial intelligence. Far less frequent—if at all—are operational applications of ethics code in the innovation, practice, and policy of AI. To date, the focus of attention is on scientific and technical advances as well as enhanced computational advances.

Especially important in this connection has been the pervasive “ethics-in-AI gap,” that is, the near absence of attention paid to matters of ethics in Artificial Intelligence. At this point, there is a growing recognition that ethical issues cannot be ignored. Some have issued formal statements expressing their corporate position. Others, like Amazon, Google, Facebook, IBM, and Microsoft are collaborating to develop best practices in AI. Governments are gradually turning to these issues as well.

Of relevance here are the OECD’s AI Policy Observatory and the European Commission’s High-level Group on Artificial Intelligence, as well as the United States Commission on Artificial Intelligence.

Background

As part of our background investigations, we have (a) identified and reviewed a large number of statement-as-formal-policy on ethics in AI in both the private and public sectors worldwide and (b) systematically recorded their central features.

We have also (1) identified countries with formal AI policies and (2) created systematic records central features.

Yet to be examined is any relationship between AI policy on the one hand, and AI capability on the other. Of importance is capturing systematic relationship (if any) between:

- AI policy and AI capability;

- AI capability and level of economic development; and

- AI capability and content of AI activity.

Purpose & Premises

The basic proposition underlying this initiative is that the parameters for agreement on ethics in artificial intelligence remain largely uncharted and fraught with diverse types of unknowns. Our purpose is to anchor ethics in AI in a multidimensional context to facilitate alignment of AI ethics and AI practice.

Basic premises include (i) ethics as a central feature of any emergent international agreement on AI (ii) no constraints on research and exploring the “unknown rights (iii) Close review and assessment of machine-brain interactions (or interface systems) and (iv) attention must be given to culturally-based ethical considerations.

To reduce the dangers of undue simplification, or the trap of “one size fits all,” and to avoid implicit bias, we use four distinct, but interconnected, imperatives as a “basic checklist “and methodological guidance, to ensure that we remain on course, working towards an integrated and coherent system of “Ethics-in-AI.” These are:

- Domains of Interaction,

- Dimensions of Analysis,

- Levels of Analysis, and

- Fundamentals of Foundations.

Jointly these features provide solid basis for a robust framing of “Ethics-in-AI”

Program Activities & Expected Value

The proposed initiative consists of five activities, each designed to yield specific value added:

- AI General “State of the Art” to yield a comprehensive and “best review” on ethics-in-AI. The value lies in creating a “system boundary” for the substantive inquiry and issues raised in the program design as a whole.

- Situating Ethics to identify the content of stated Ethics-in-AI and create of a database organized by key variables and sources. The value-added is distinguishing between aspirational and operational postures on ethics.

- Policy Analytics for Ethics-in-AI to generate an empirical database of AI policy structure, substantive content, as well as embedded features. The value-added lies in aggregating results to identify central tendencies, outliers, and other features.

- Ontology of Ethics-in-AI to create an empirically based structured ontology of ethics-in-AI the database. The value-added is a searchable knowledge repository.

- Ethics in AI and National Profiles to identify the statistical relationships (if any) between AI policies and state profiles (i.e., empirical features). The value-added lies in locating potential national propensities for particular Ethics-in-AI configurations.

Governance refers to the underlying principles for overseeing the control or direction of an organized entity. By contrast, government refers to the institution for operations and implementation of decision.

Here we address foundations and basics for governance of AI (focusing on the “body” of AI-functions) as well as and for government by AI (focusing on AI-assisted provision of services).

Governance of AI – AIWS Model

This initiative is an early version of efforts to highlight critical features in the formation of AI-Government. Prepared for AIWS.net by Dukakis et al. (2018a). Selections of the Report are summarized below.

The initiative is anchored in the assumption that humans are ultimately accountable for the development and use of AI, and must therefore preserve that accountability. Hence, it stresses transparency of AI reasoning, applications, and decision making, as well as embedded auditability.

The goal is to create the AI society, is defined as a society consisting of all objects with the characteristics of Artificial Intelligence. Any object in this society is an AI Citizen. Rules are needed to govern the behaviors of AI Citizens, as there are rules that govern human behavior in a social system, members of society. The focus is primarily on AI development and resources needs, including data governance, accountability, standards, and the responsibilities of practitioners (e.g., Alexa and Google Home), and others.

The AIWS model establishes a set of norms and best practices for the development, management, and uses of AI so as ensure safety and security for all. It seeks to provide a baseline for guiding AI development to ensure positive outcomes and to reduce pervasive and realistic risks and related harms that AI could pose to humanity.

Government by AI – Provision of Services

This initiative is an early version of efforts to highlight critical features in the formation of AI-Government to provide public services. Prepared for AIWS.net by Dukakis et al. (2018b).

AI cannot replace governance by humans or human decisional processes but it t can help guide and inform guides and informs them, while providing preferred bases for service provision and evaluation. AI supported public services span major critical functions to support all functions in society and all necessary services.

- Automated public services assisted by AI, and

- Tasks required to establish AI-Government

Reference:

- Dukakis, M., Choucri, N., Cytryn, A., Jones, A., Nguyen, T. A., Patterson, T., Reveron, D., & Silbersweig, D. (2018a). The AIWS 7-layer model to build next generation democracy. BGF-G7 Summit 2018. The Boston Global Forum, & Michael Dukakis Institute for Leadership and Innovation. http://bostonglobalforum.org/wp-content/uploads/The-BGF-G7-Summit-Report.pdf

- Dukakis, M., Nguyen, T. A., Choucri, N., & Patterson, T. (2018b). The concept of AI-government: Core concepts for the design of AI-government (Concept Paper). Boston Global Forum, & Michael Dukakis Institute for Leadership and Innovation. http://bostonglobalforum.org/mdi/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/AI-Government-version-1.0.pdf

It is already evident that an AI state policy ecosystem is developing, albeit still at a relatively early stage. Here we highlight policy content (in formal terms) as well as select reviews by analysts (of formal state positions). This work is at an early state. It focuses on the “raw data” analyzed by MIT research assistants, and covers:

- National AI policies of states currently recorded, including of AI state policies as presented in official publications and highlights of common themes.

- Comparative analysis of AI policies of states as reported in official publications based on published surveys of AI policies and postures.

The initial data base presents the high-level features of each case.