Cyberspace necessitates major departures from structure and process in international relations. This new domain of interaction is a source of vulnerability, a potential threat to national security, and a disturber of the familiar international order. Such simple rendering notwithstanding, it is clear to see the potential disconnects between these basic principles and the character and ubiquity of cyberspace.

There are inherent tensions that are yet to be addressed. Efforts to extend, or apply international law to cyberspace—notably Tallinn Manual 2.0 (Schmitt 2017)—reflect the view of international legal experts with all the assumptions of state and territoriality. One analyst argues that there is a "simple choice"—between "[m]ore global law and a less global internet" (Kohl 2007, 28-30).

Among the new imperatives for theory, policy, and practice—and especially for basic research—at least four require special attention:

If we take into account the salience of cyberspace—especially the dramatic expansion of cyber access in all parts of the world, the growth in “voicing” and cyber participation, or the new opportunities provided by uses of cyber venues—then we can appreciate the fundamental departures from tradition in international structures and processes, and that the world is now much more complex. All of this creates new challenges for the state system.

Especially important here is that characteristic features of cyberspace stand in sharp contrast to our traditional conceptions of social systems generally, and to the state system in particular. We must signal the critical disconnects between the key features of interactions in cyberspace and the traditional features of the international system. Shown in the Table below are properties of the cyber domain that are particularly vexing for the state system (Choucri 2012).

| Temporality | Introduces near-instantaneousness into high politics |

| Physicality | Transcends physical constraints |

| Permeation | Penetrates boundaries and jurisdictions |

| Fluidity |

Sustains shifts and reconfigurations |

| Participation | Reduces barriers to political expression |

| Attribution | Obscures actor identity and links to action |

| Accountability | Bypasses established mechanisms |

| Source: Based on Choucri (2012, 4). | |

All of this becomes increasingly important given that who gets what, when, and how is influenced by cyber access, as well as by the groth and diversity of actors, each endowed with differential levels and distributions of traditional power and capability. By definition, all entities generate demands (that they seek to meet) and are endowed with capabilities (that they chose to deploy). They are all able to participate in one way or another in international deliberations, and all seek venues for shaping the evolving international political agenda—but only nation-states have the right to vote.

Early in the 21st century, it was already apparent that the cyber domain shaped new parameters of international relations and new dimensions of international politics. The "new normal" for world politics in the cyber age includes the state system, to be sure, it also includes a wide range of nonstate entities—known and unknown—all of whom operate in a highly dynamic and volatile international context.

References:

- Choucri, N. (2012). Cyberpolitics in international relations

. MIT Press.

- Kohl, U. (2007). Jurisdiction and the Internet: A study of regulatory competence over online activity

. Cambridge University Press.

- Schmitt, M. N. (Ed.). (2017).Tallinn manual 2.0 on the international law applicable to cyber operations

. Cambridge University Press.

The “new normal” in world politics in the cyber age involves the state system, to be sure, as well as the wide range of non-state entities—known and unknown—all of whom operate in a highly dynamic and volatile international context. It is a context that limits the efficacy of traditional notions of deterrence—the concept and the practice. Tradition assumes knowledge of the identity of the adversary. This is seldom the case at this point. In short, the “new normal” is hardly consistent with the standard textbook of international politics anchored in a state system that has a monopoly over the use of force, where force is defined in kinetic terms.

All of this creates an overarching and inescapable challenge for the state, the state system, and international relations. The challenge is how to manage the entire security complex given the emergence of unprecedented forms of threat to security (cyber threats) that signal new vulnerabilities (undermining cybersecurity) and – most vexing of all – emanating from unknown sources (a feature which we refer to as the attribution problem). All of this inevitably reinforces the politicization of cyberspace and its salience in emergent policy discourses.

It goes without saying that all of this forces us to re-assess the conventional perspectives on security, as threats to cyber security become more and more salient. But this is only one side of the proverbial coin when seen in an international perspective. The other side of the equally proverbial coin is about cooperation and the challenges associated with international governance, especially governance of cyberspace. The complexities at hand are exacerbated by differences in rates of change: cyberspace is evolving much faster than are the tools of the state to regulate it. They both change, but at different rates. Also important is the “nature” of the evolutionary drivers, that is, whether they are endogenous, that is generated by the R&D system or exogenous to the R&D system and even the domain at hand.

It may well be that changes in one domain—cyberspace or the international system—induce changes in the other. It is unlikely that any change can be attributed entirely to system-specific or endogenous factors. It goes without saying that differences in speed are foundational in any consideration of co-evolution. This is taken for granted, yet to be developed are methods for measuring such differences. We do not anticipate, nor hypothesize, mirror-image dynamics across physical and cyber domains, nor can we even consider the possibility of identical adjustments over time. But we posit that temporal differences go a long way in shaping the nature of co-evolution—the leads and lags, feedback, and other critical systemic features.

All of this creates an overarching and inescapable challenge for the state, the state system, and international relations—what are the similarities or differences between the "rea" and the cyber systems?

This leads us to two questions: first, do state profiles in the cyber domain mirror those in the traditional or “real” world? Are the observed patterns of change in a state’s location in the “real” profile “space” similar to those in the cyber domain? These questions are now at the core of lateral pressure theory. This means that cyber-metrics must be developed and, to the extent possible, carry the same “meaning” as in the traditional domain.

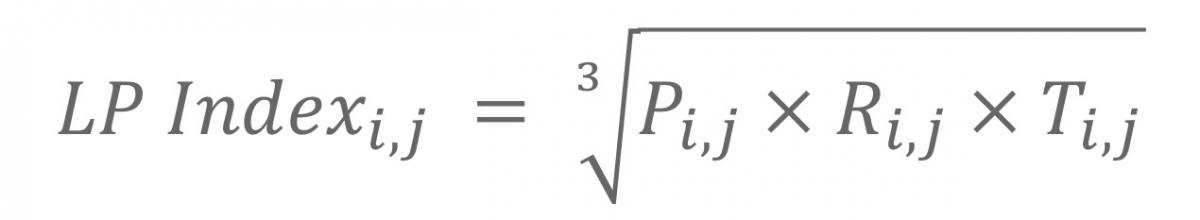

More recently we developed the Lateral Pressure Index in order to quantify propensity for expansion and, to the extent possible, to highlight the relative salience of individual drivers. After some experimentation, we framed the Lateral Pressure Index as a function of the geometric mean of its master variables:

where

Pi,j, Ri,j, and Ti,j as population-, resource- and technology- master variables for country i at time respectively.

See Research